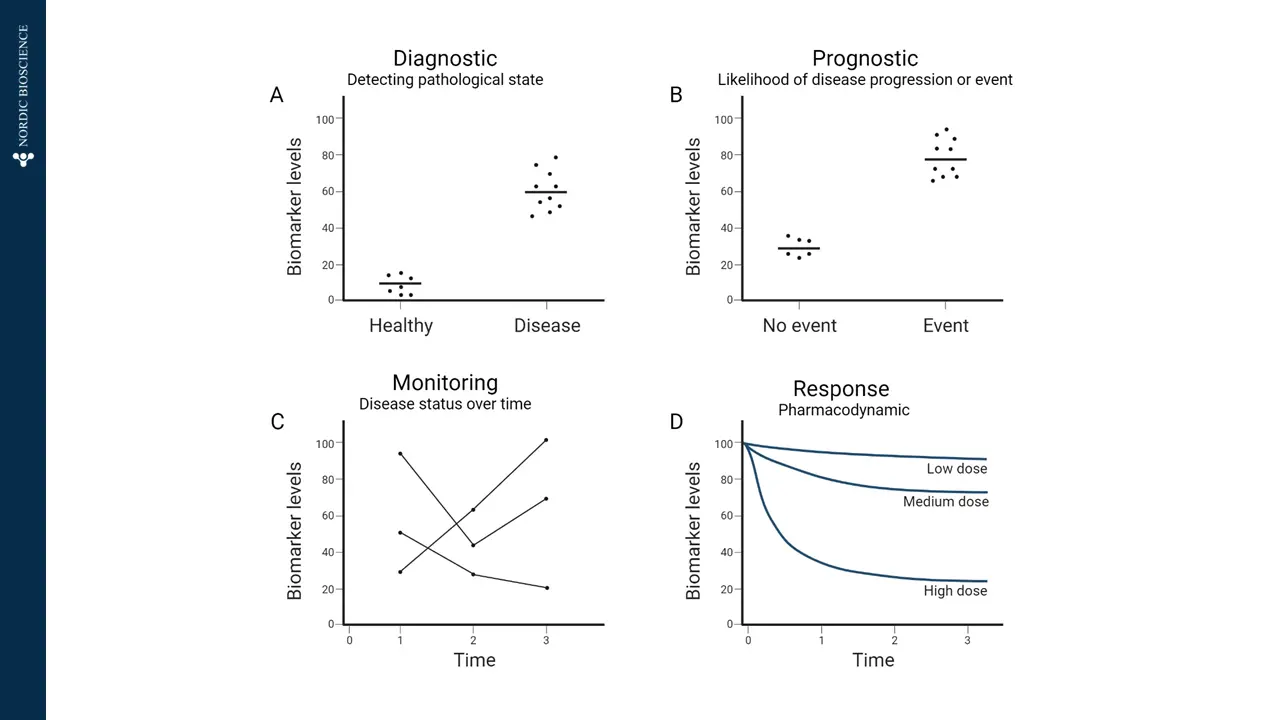

Effective and objective evaluation of biological processes are essential components of evaluating patients, particularly in the context of drug development. Biomarkers are essential components in this regard.

However, in order to translate the results provided by biomarkers, regulators and clinical trialists alike require unambiguous interpretation and communication.

To address this, the FDA-NIH Joint Leadership Council established a framework and vocabulary for how biomarkers can be interpreted, including their use and their significance: the Biomarkers, EndpointS, and other Tools (BEST) glossary.